By Milton Kirby | Atlanta, GA | October 18, 2025

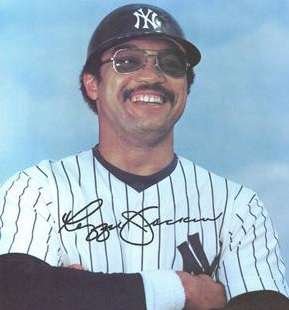

A night that named a legend

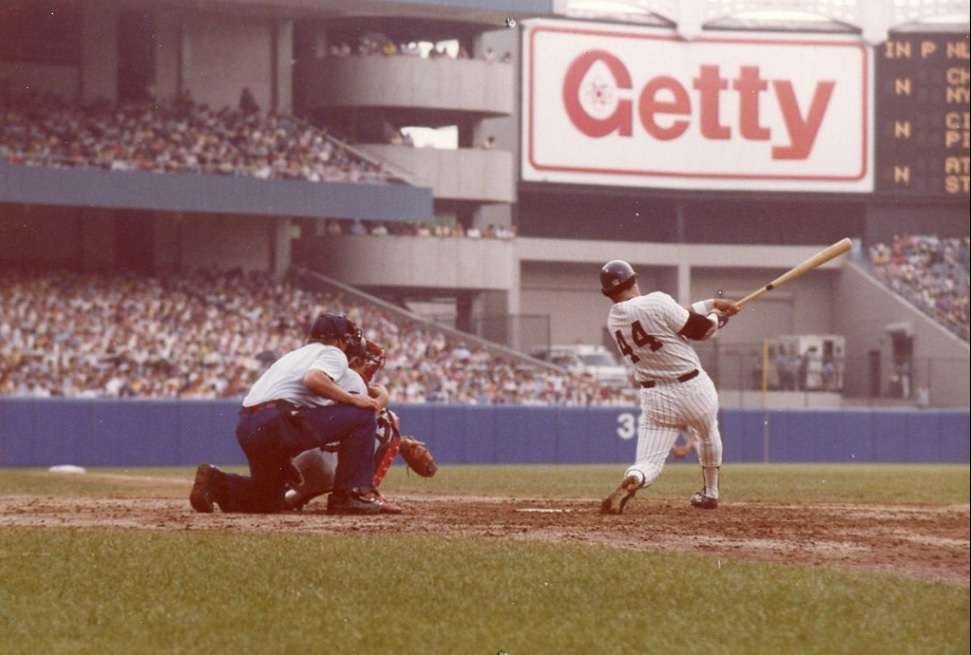

On Oct. 18, 1977, Reggie Jackson stepped into Yankee Stadium history. He saw three first-pitch strikes. He launched all three into the seats. The third flew to deep center, off the black batter’s eye. The Yankees clinched the World Series. The crowd roared “Reg-GIE!” and a nickname stuck forever: Mr. October.

That moment didn’t come easy. Jackson had joined New York after a stormy year in Baltimore. The Yankees clubhouse ran hot: big egos, bigger expectations. Manager Billy Martin benched him in the ALCS, then called his number late. Jackson answered with a key RBI single. He carried that momentum into the World Series—five home runs in the final three games, eight RBI, and a record 25 total bases. He owned October.

Built for big stages

Reginald “Reggie” Martinez Jackson played 21 MLB seasons. He starred for the Kansas City/Oakland A’s, Baltimore Orioles, New York Yankees, and California Angels. He was a 14-time All-Star, the 1973 AL MVP, a five-time World Series champion, and a two-time World Series MVP. He finished with 563 home runs and a reputation for rising when it mattered most.

He also led the league in strikeouts—proof that taking big swings cuts both ways. But teams got better around him. Across two decades, Jackson’s clubs finished first 11 times and endured only two losing seasons. The A’s won three straight titles from 1972–74. The Yankees won back-to-back in 1977–78. The Angels won division crowns in 1982 and 1986. New York retired his No. 44 in 1993; Oakland retired his No. 9 in 2004. He entered the Hall of Fame in 1993.

The early fight: talent, tests, and grit

Jackson grew up in Wyncote, Pennsylvania, the son of Martinez Jackson, a former Negro Leagues infielder. At Cheltenham High, Reggie starred in four sports. Football nearly ended his athletic career—neck fractures, weeks in the hospital, a bleak prognosis. He came back anyway.

Major programs recruited him for football. He chose Arizona State, aiming to play both football and baseball. The pros soon called. In the 1966 draft, the A’s took him second overall. He signed, climbed quickly, and debuted in 1967. Two years later he clubbed 47 homers and chased Ruth and Maris for a summer.

Oakland greatness, Oakland grit

With the A’s, Jackson helped build a dynasty. From 1971–74, Oakland stacked division titles and won three straight World Series. He hit, he ran, he argued, he won. He blasted a transformer with a thunderous 1971 All-Star homer in Detroit. He stole home to help clinch the 1972 AL pennant—tearing his hamstring in the process and missing the Series the A’s still won.

Oakland was talent and turbulence. Owner Charlie Finley staged a “Mustache Day.” Teammates brawled. Arbitration battles made headlines. Through it all, Jackson produced—254 homers in nine A’s seasons—and forced the sport to deal with a star who wouldn’t shrink.

The Making of Mr. October

New York magnified everything. The media glare was constant. Quotes cut both ways. A June 1977 dugout confrontation with Billy Martin played out on national TV. Yet when the stakes rose, Jackson delivered. He crushed a walk-off-style dagger against Boston in a tense September race. Then came that three-homer masterpiece in Game 6. In 1978, he did it again—homers when needed most, a second straight title, and a legend cemented.

Legacy: power, pressure, contradictions

Jackson’s career tells a full American sports story. He won big. He failed big. He spoke his mind. He shouldered heat others couldn’t. He made teammates and cities better. He was the first to hit 100 home runs for three different franchises. He stacked rings and records while carrying the burdens of fame, race, and expectation in a volatile era.

Giving back: the Mr. October Foundation

After baseball, Jackson advised the Yankees for years, then joined the Astros as a special advisor in 2021. Off the field, he leaned into service. The Mr. October Foundation focuses on science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM education and career pathways for underserved youth. The mission is practical and urgent: connect students to real-world skills in engineering, advanced manufacturing, medical fields, and the trades.

Since 2014, the foundation has partnered with STEM 101, launching first in the Bronx (2015) and expanding to Detroit, Oakland, and St. Louis. The program’s three pillars—Create & Innovate, Career Pathways, andSolutions-Based Learning—turn curiosity into competence. The outcomes are clear: stronger post-secondary readiness, a visible path to good jobs, and a rising interest in STEM compared to peers. It’s the same formula that made Mr. October: preparation, courage, and timely impact.

Remembering where he stood—and stands

Jackson has always been candid about the business and the bruise of the game—about race, pressure, and the costs of being first in certain rooms. At baseball’s Rickwood Field tribute in 2024, he spoke bluntly about the insults and exclusions he faced early in his career. Those memories still cut. Yet his story arcs toward construction: hitting through hecklers, winning through chaos, building programs that open doors for kids who will build what’s next.

Why Mr. October still matters

Reggie Jackson is more than a night of three swings. He is a career of big moments and a life of bigger meaning. He pushed baseball forward. Now he’s pulling students forward—toward the labs, shops, clinics, and plants where the next American breakthroughs will be made. That’s clutch, too.

Related articles:

Baseball Historian Ted Knorr Brings Negro League Legacy to Life in new TSJ Column

From Exclusion to Excellence: The Birth of Negro League Baseball

Shadow Ball: Learning More About Negro League History

Why Rap Dixon Belongs in Cooperstown with the Legends

Negro League Conference Unveils More History and Takes on Future Challenges

Willie Mays, Baseball Legend and Hall of Famer, Passes Away at 93

Please consider supporting open, independent journalism – no contribution is too small!