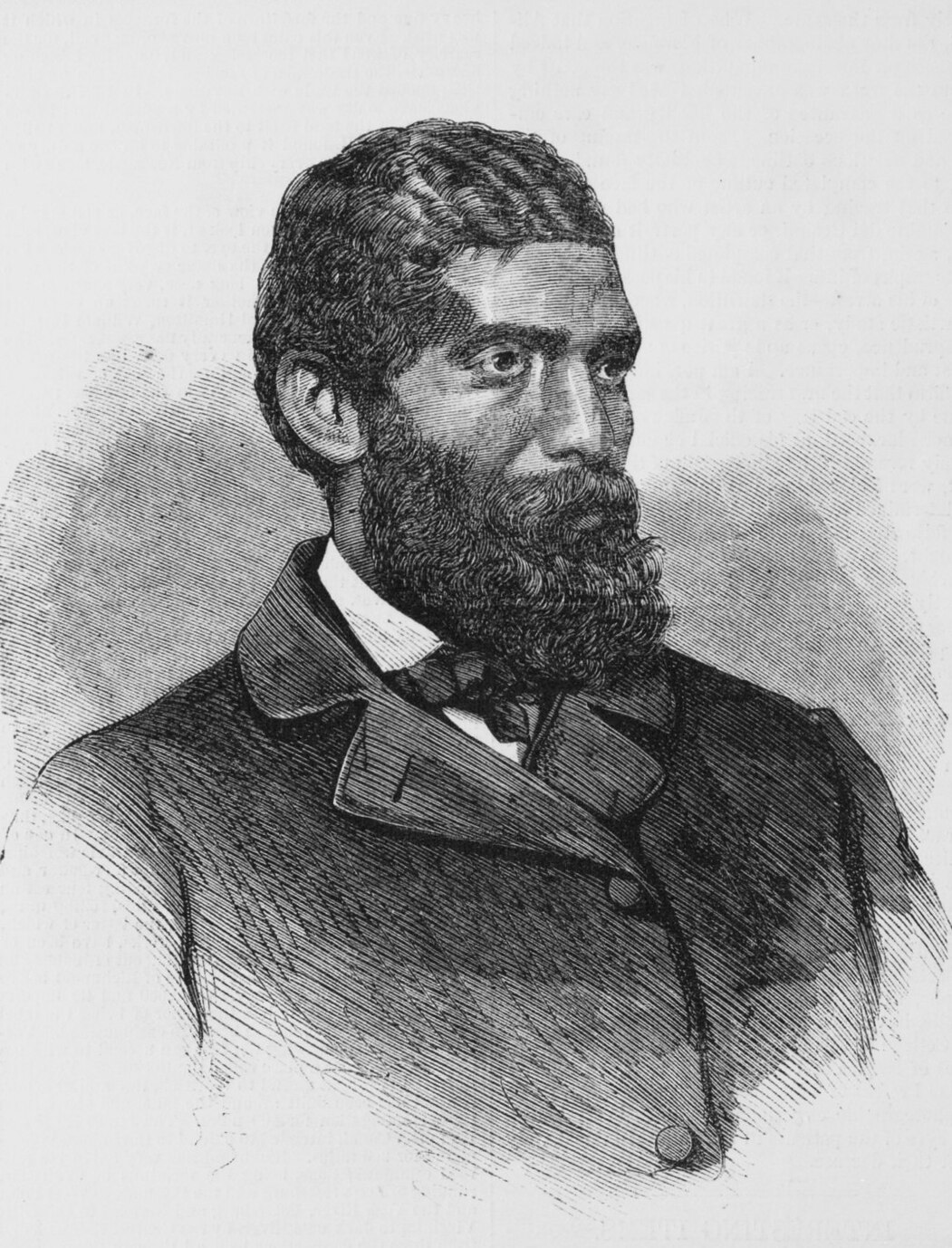

Physician. Dentist. Lawyer. Abolitionist. Pioneer of Black dignity.

Born: October 13, 1825 — Died: December 3, 1866

By Milton Kirby | Atlanta, GA | February 1, 2026

Long before the civil rights movements of the 1960s, John Stewart Rock stood in the cradle of liberty, Boston’s Faneuil Hall, and demanded that the nation recognize not only the humanity of Black people but also the race’s inherent beauty, intellect, and strength. At a moment when the Supreme Court had attempted to erase Black citizenship through the Dred Scott decision, Rock asserted a higher authority: the undeniable truth of his own identity and the dignity of his people.

His March 5, 1858, address was both scholarly and incendiary. Drawing on his medical training, he dismantled the era’s so-called “scientific” racism, rejecting the notion that whiteness defined beauty or superiority. Instead, he celebrated what he called the “beautiful, rich color” of Black people and argued that true excellence was measured by character and resilience, not complexion.

Even more provocative was Rock’s call for self-determination. He urged Black Americans to rely on their own strength — to “sink or swim” with their race — and to build institutions, intellect, and dignity from within. It was a philosophy rooted in pride, discipline, and an unshakable belief in Black potential. That worldview would guide every chapter of his remarkable life.

In the landscape of 19th-century America, a nation fractured by slavery, war, and racial hierarchy, few figures embodied intellectual defiance and quiet excellence like John Stewart Rock. Born free in Salem, New Jersey, Rock rose to prominence not through wealth or political power, but through relentless study, disciplined mastery, and an unwavering belief in the inherent worth of Black people. His life stands as one of the most extraordinary examples of Black professional achievement before the end of the Civil War.

Denied admission to medical school because of his race, Rock refused to be deterred. He apprenticed under two white physicians in Philadelphia, studying medicine the way many Black professionals of the era were forced to — through private mentorship rather than institutional access. When medical opportunities remained limited, he pivoted to dentistry, quickly earning a reputation for precision and skill. His success eventually opened the door to formal medical study, and Rock earned his medical degree, becoming one of the earliest African American physicians in the United States.

While practicing medicine and dentistry, Rock emerged as a commanding abolitionist speaker whose words cut through the political fog of the era. In his 1858 address, he declared:

“I am proud of my ancestry. I am proud of the black man… I believe that the time will come when the black man will be as much respected in this country as the white man is.”

His speeches consistently confronted the myth of white superiority, reminding audiences that oppression was not evidence of inferiority, but of injustice.

Years of overwork and declining health eventually forced Rock to scale back his medical practice. But instead of retreating, he reinvented himself once again, this time as a lawyer. He studied law with the same intensity he had brought to medicine and was admitted to the Massachusetts bar, offering representation and advocacy to Black clients navigating a hostile legal system.

On February 1, 1865, in the final months of the Civil War, Rock became the first Black attorney admitted to practice before the United States Supreme Court. The moment represented the intellectual authority of a people long denied recognition and signaled a shift in the nation’s legal and moral landscape as the 13th Amendment moved toward ratification.

Rock’s health continued to decline, and he died on December 3, 1866, at just 41 years old. Though his life was brief, his impact was profound. His speeches, including his reflections on the Haitian Revolution.

“The history of the bloody struggles for freedom in Hayti… will be a lasting refutation of the malicious aspersions of our enemies.”

reveal a man deeply aware of the global Black struggle for dignity and liberation.

John Stewart Rock’s life is a reminder that brilliance often emerges in the margins — in the quiet determination of individuals who refuse to accept the limits imposed upon them. His achievements challenge the historical narrative that Black excellence began after emancipation.

Rock proved, long before the Civil War ended, that Black intellect, discipline, and leadership were already reshaping the nation.

John Stewart Rock at a Glance

Key Dates

• 1825 — Born free in Salem, New Jersey

• 1844–1848 — Teacher in New Jersey public schools

• 1852 — Earns medical degree

• 1855 — Admitted to the Massachusetts bar

• 1858 — Delivers landmark Crispus Attucks Day address at Faneuil Hall

• 1865 — First Black attorney admitted to the U.S. Supreme Court bar

• 1866 — Dies at age 41

Signature Ideas

“Beautiful, rich color.”

Rock’s rejection of “scientific” racism and his affirmation of Black beauty decades before the phrase Black is beautiful entered the cultural lexicon.

“Sink or swim with our race.”

His call for Black self-determination, institution building, and intellectual independence.

“A lasting refutation.”

His insistence that Haiti’s revolution proved Black capability and courage on the world stage.

Professional Firsts

• Among the earliest African American physicians

• Practiced both medicine and dentistry

• One of the first Black lawyers in Massachusetts

• First Black attorney admitted to argue before the U.S. Supreme Court

Why He Matters

Rock’s life demonstrates that Black excellence did not begin with emancipation — it was already flourishing in the shadows of slavery. His achievements challenge the nation’s historical amnesia and reclaim a lineage of brilliance too often overlooked.

“I am proud of my ancestry. I am proud of the black man.”

— John Stewart Rock, 1858

Truth Seekers Journal thrives because of readers like you. Join us in sustaining independent voices.