By Milton Kirby | Montgomery, AL | December 1, 2025

A quiet act that shook a city

Seventy years ago in Montgomery, Alabama, a soft-spoken seamstress made a choice that changed the course of American history.

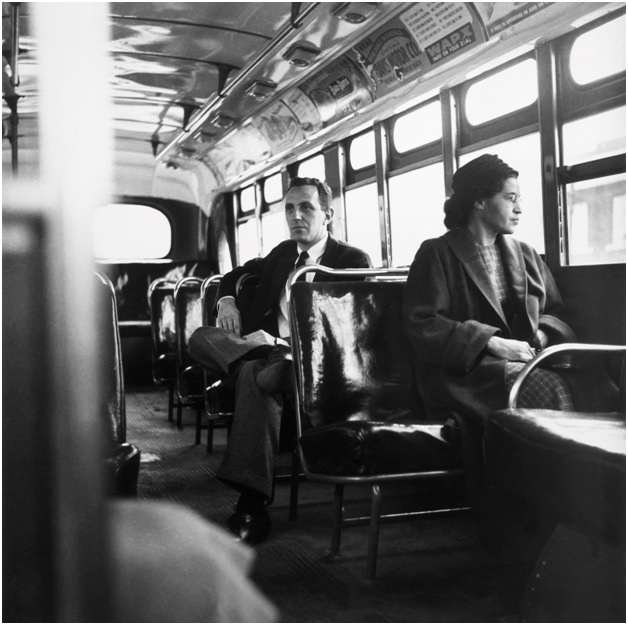

On December 1, 1955, 42-year-old Rosa Louise McCauley Parks refused bus driver James F. Blake’s order to give up her seat so a white man could sit. Montgomery’s rules reserved the front rows for white riders and pushed Black passengers to the back. The middle seats, where Parks sat, were a constant battleground.

Three Black riders in her row stood up. Parks did not.

“I felt that, if I did stand up, it meant that I approved of the way I was being treated, and I did not approve,” she later said. She was not too tired from work; she was “tired of giving in.”

Police were called. Parks was arrested, fingerprinted, fined, and pushed into the machinery of Jim Crow justice. But what happened next turned one woman’s arrest into a mass movement.

The Montgomery Bus Boycott: 381 days of organized courage

Parks’ arrest hit a nerve in a city where Black riders made up about three-fourths of bus passengers but had few rights on board. For decades, drivers had ordered Black passengers to stand, even when seats were open. Many drivers carried weapons and had near-police authority on their routes.

This time, the community pushed back.

The Women’s Political Council quickly circulated tens of thousands of leaflets calling for a one-day bus boycott on the day of Parks’ trial, December 5, 1955. Black residents walked, carpooled, and paid Black taxi drivers instead of riding city buses. Courtroom benches were full. Bus seats were nearly empty.

That same evening, thousands crowded into Holt Street Baptist Church. Local ministers and organizers formed a new group, the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA), and chose a young pastor, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, as president.

They voted to keep the boycott going. Day after day, for 381 days, Black residents of Montgomery walked miles to work and to school. Volunteers ran car-pool systems. Church parking lots became dispatch centers.

The city tried to break the movement. Parks lost her job as a seamstress. Her husband, Raymond, was fired as well. Leaders were arrested and threatened. A grand jury declared the boycott illegal. Still, people kept walking.

In federal court, a separate case, Browder v. Gayle, challenged bus segregation directly. In November 1956, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that segregation on Montgomery’s buses was unconstitutional. On December 20, 1956, the court’s order took effect. Dr. King called off the boycott. The next day, Black riders boarded buses and sat wherever they chose.

A quiet “no” had turned into a landmark victory that propelled the national Civil Rights Movement.

Years of organizing before the bus ride

The popular story often begins with a tired seamstress on a December afternoon. But Parks’ courage was not sudden. It was built over years of steady, often dangerous work.

Parks joined the Montgomery chapter of the NAACP in 1943 and soon became its secretary. She attended meetings, took notes, and listened. She and her husband were active in the local Voters League, struggling to increase Black voter registration at a time when poll taxes, literacy tests, and intimidation kept almost all Black citizens from the rolls.

Parks herself tried three times to register to vote before finally succeeding in 1945.

As NAACP secretary, she helped investigate violent crimes that white authorities preferred to ignore. In 1944, she took on the case of Recy Taylor, a Black woman from Abbeville who was kidnapped and gang-raped by white men. When local juries refused to indict the attackers, Parks and other activists organized the Committee for Equal Justice for Mrs. Recy Taylor, building one of the strongest national campaigns against racial and sexual violence in that era.

She also worked for justice in the case of Jeremiah Reeves, a Black teenager accused of raping a white woman and later executed.

In the summer of 1955, just months before her arrest, Parks attended training at the Highlander Folk School in Tennessee, an interracial education center where activists studied nonviolent protest and community organizing. That experience, she later said, helped strengthen her resolve.

By the time she sat down on that bus in December 1955, Rosa Parks was not just a seamstress. She was a seasoned organizer who understood both the risk and the power of civil disobedience.

Roots of resistance: family, school, and early Jim Crow

Rosa Louise McCauley was born in Tuskegee, Alabama, on February 4, 1913. Her parents, James and Leona McCauley, separated when she was young. Rosa and her younger brother, Sylvester, were raised mainly by her mother and maternal grandparents near Montgomery.

Her grandparents were formerly enslaved people who believed fiercely in racial equality. They kept a shotgun by the door and refused to shrink from white terror. Growing up in their home, Parks learned both the fear and the pride that came with resisting injustice.

She attended the laboratory school at Alabama State College, an unusual opportunity for a Black girl in the 1920s. Later, she worked to complete her education, earning her high school diploma in 1933 at a time when only about 7% of Black Alabamians had finished high school.

During World War II, Parks worked at Maxwell Air Force Base in Montgomery. On base, the buses were integrated, and she could ride alongside white co-workers. Off base, she had to return to segregated city buses. That painful contrast, she later said, “opened her eyes” to the unnatural cruelty of Jim Crow.

In 1932, she married Raymond Parks, a barber and early NAACP activist. With his encouragement, she returned to school and deepened her activism. Their small home became a place where politics and community strategy were regular topics at the kitchen table.

The personal cost—and new beginnings in Detroit

The boycott’s success came at a high cost for Parks and her family. In addition to the firings and constant threats, she and Raymond struggled to find work in Montgomery afterward. The city that had celebrated her as a symbol elsewhere often treated her as a troublemaker at home.

In 1957, the couple moved north to Detroit, Michigan, looking for safety and opportunity. Even there, they found neighborhoods divided by race and an economy that still treated Black families unfairly. Parks continued her work quietly—speaking, organizing, and supporting local struggles against school segregation, housing discrimination, and police brutality.

From 1965 to 1988, she worked as a staff assistant for U.S. Congressman John Conyers Jr. Her desk in his Detroit office became a quiet but powerful bridge between local residents and the halls of Congress. Through this job, her influence reached into the federal government and helped shape responses to civil rights issues in the North as well as the South.

Building leaders: The Rosa and Raymond Parks Institute

In 1987, Parks co-founded the Rosa and Raymond Parks Institute for Self-Development. The institute focuses on youth leadership, voter education, and teaching civil rights history. Its “Pathways to Freedom” programs take young people on bus tours through key civil rights sites, helping them see that history is not just something in a textbook—it is written by ordinary people who refuse to accept injustice.

By then, the nation had begun to give Rosa Parks the honors her work deserved. She received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1996 and the Congressional Gold Medal in 1999. Textbooks called her the “mother of the modern Civil Rights Movement.” For many schoolchildren, her story became their first lesson in civil disobedience.

Inspiring new movements: from Montgomery to disability rights

Parks’ influence did not end with racial desegregation. Her example helped later generations see public transportation as a stage for justice.

In 1984, in Chicago, disability rights activists from the group ADAPT rolled their wheelchairs in front of city buses to protest the purchase of hundreds of new vehicles without wheelchair lifts. Like Parks, they were demanding the right simply to ride. Their actions helped build support for accessible transit and laid groundwork for the Americans with Disabilities Act.

Their protest echoed Parks’ lesson: organized, nonviolent disruption can force a city—and a nation—to confront who is left behind.

Final honors and a living legacy

Rosa Parks died in Detroit on October 24, 2005, at the age of 92. In death, she received an honor no woman in U.S. history had ever received before: her body lay in honor in the rotunda of the U.S. Capitol. Thousands lined up in silence to pay their respects.

Today, buses, schools, streets, and museums bear her name. But her deepest legacy lives in something smaller and harder to measure: the courage of ordinary people who refuse to “give in” when the rules are unjust.

Each year, walkers trace the short route from Dexter Avenue King Memorial Baptist Church to the Rosa Parks Museum in Montgomery. The distance is only a few city blocks. The meaning stretches across generations.

It is a reminder that one woman’s quiet “no,” backed by years of organizing and a city willing to stand with her, can bend the arc of history—and still speaks to struggles for justice today.

Related articles

Thurgood Marshall: The People’s Lawyer Who Became America’s First Black Supreme Court Justice

Broadway Royalty and Civil Rights Warrior: Lena Horne Remembered

Brown v. Board of Education: The Supreme Court Ruling That Changed America

A Life of Grace and Grit: The Legacy of Coretta Scott King

Loretta Green, 89, Wears Her Poll Tax Certificate as a Badge of Perseverance

Support open, independent journalism—your contribution helps us tell the stories that matter most.