By Milton Kirby | Washington, D.C. | October 2, 2025

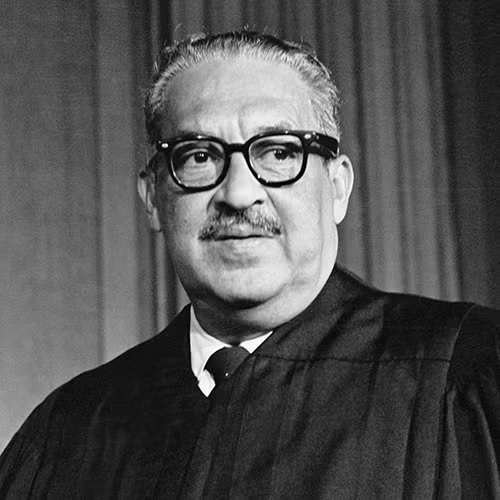

Fifty-eight years ago today, the marble halls of the U.S. Supreme Court bore witness to a moment that reshaped American history. On October 2, 1967, Thurgood Marshall raised his right hand and swore the oath of office, becoming the first African American justice to serve on the nation’s highest court.

For many watching, the image was more than ceremonial. It was the realization of a dream born from centuries of struggle — a Black man ascending to the bench of an institution that had once sanctioned slavery, segregation, and the denial of equal rights.

President Lyndon B. Johnson, who nominated Marshall just months earlier, called it “the right man, at the right time, in the right place.” In Marshall, America had found a justice who carried the Constitution not only in his mind but etched deeply into his lived experience.

From Baltimore Streets to Legal Scholar

Born in Baltimore on July 2, 1908, Marshall’s journey to the Supreme Court began in a household that valued both discipline and education. His father, William, a railroad porter, often debated court cases at the dinner table. His mother, Norma, an elementary school teacher, nurtured a love of learning.

As a mischievous schoolboy, Marshall was once punished by being forced to memorize the entire U.S. Constitution. The lesson stuck. Decades later, he joked he could still recite it word for word — but it also planted the seed of his life’s mission: to hold America accountable to its own promises.

Marshall attended Lincoln University in Pennsylvania, graduating in 1930. He then enrolled at Howard University School of Law, where he studied under Charles Hamilton Houston, a brilliant strategist who believed lawyers must serve as “social engineers.” Houston instilled in Marshall a conviction that the courtroom could be a battlefield against injustice.

“Mr. Civil Rights”

By the mid-1930s, Marshall had joined the NAACP and quickly rose to become its chief counsel. His legal work became the backbone of the civil rights movement. Over the course of his career, Marshall argued 32 cases before the Supreme Court — and won 29 of them.

His most famous victory came in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), where he persuaded the Court to strike down segregation in public schools. The unanimous decision overturned the Plessy v. Ferguson “separate but equal” doctrine and became a cornerstone of the modern civil rights era.

But Brown was just one milestone. In Smith v. Allwright (1944), Marshall dismantled the “white primary” system that excluded Black voters. In Sweatt v. Painter (1950), he challenged unequal law school facilities, a precursor to broader desegregation. Earlier, in Chambers v. Florida (1940), he defended Black men coerced into confessing murder.

Through relentless litigation, Marshall became known as “Mr. Civil Rights” — a lawyer who used the Constitution as both shield and sword against Jim Crow.

“In recognizing the humanity of our fellow beings,” Marshall once said, “we pay ourselves the highest tribute.”

A Judge and Solicitor General

Marshall’s impact extended beyond the NAACP. In 1961, President John F. Kennedy appointed him to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. Four years later, President Johnson tapped him as the nation’s first Black Solicitor General — the government’s top lawyer before the Supreme Court.

In that role, Marshall argued 19 cases and won 14. His victories ranged from labor rights to antitrust law, further cementing his reputation as one of the era’s most formidable legal minds.

Johnson saw Marshall’s elevation to the Supreme Court as a natural progression. “I believe he has earned that appointment. I believe he deserves it,” the president declared when he announced the nomination in June 1967.

A Historic Confirmation

Marshall’s confirmation hearings before the Senate Judiciary Committee were contentious. Some senators pressed him aggressively on criminal justice issues, while Southern opponents masked their discomfort with questions about his qualifications.

But Marshall’s calm, thorough answers won the day. On August 30, 1967, the Senate confirmed him by a vote of 69 to 11. Two months later, he was sworn in — breaking a barrier that had stood since the Court’s founding in 1789.

For millions of Black Americans, Marshall’s appointment symbolized progress that once seemed unthinkable. Here was a man who had fought segregation in classrooms now seated in the chamber that set the law of the land.

“A child born to a Black mother in a state like Mississippi,” Marshall reflected, “has exactly the same rights as a white baby born to the wealthiest person in the United States. That is the principle I fought for.”

On the Bench: A Voice for the Marginalized

During his 24 years on the Court, Marshall consistently championed the rights of individuals, the poor, and the marginalized. He opposed the death penalty, arguing it was applied disproportionately against minorities and the poor.

In Furman v. Georgia (1972), Marshall sided with the majority in striking down existing death penalty statutes. In later dissents, he argued that the death penalty itself was cruel and unusual punishment.

Marshall was also a strong defender of affirmative action. In Regents of the University of California v. Bakke (1978), he argued that remedies for centuries of discrimination were both constitutional and morally necessary.

His guiding principle was simple yet profound: “Equal means getting the same thing, at the same time, and in the same place.”

Even as the Court grew more conservative in the 1970s and 1980s, Marshall’s voice remained steady. Often in dissent, he nevertheless articulated a vision of justice rooted in fairness and equality.

Retirement and Passing the Torch

Marshall retired in 1991, citing declining health. His departure marked the end of an era. President George H.W. Bush appointed Clarence Thomas, a conservative jurist, as his successor — a decision that underscored the sharp ideological shift of the Court.

Marshall passed away on January 24, 1993, at age 84. He was laid to rest in Arlington National Cemetery, honored as both a civil rights giant and a Supreme Court justice.

Legacy and Relevance Today

Marshall’s legacy reverberates through every corner of American law. Schools, courthouses, and even Baltimore/Washington International Airport bear his name. His career stands as proof that the law, when wielded with courage, can dismantle walls of oppression.

But Marshall himself was clear-eyed about the limits of the legal system. “The legal system can force open doors and sometimes even knock down walls,” he once said, “but it cannot build bridges. That job belongs to you and me.”

Today, as debates rage over voting rights, affirmative action, and racial equity, Marshall’s words carry renewed urgency. His belief in the Constitution as a “living document” — one meant to expand justice rather than freeze it in time — is echoed in current struggles to define equality in America.

Closing Reflection

October 2, 1967, was not just the day a man took an oath. It was the day a nation took a step toward becoming what its founding documents had always promised.

Thurgood Marshall’s life was proof that the Constitution, in the hands of those brave enough to demand its full measure, could be both weapon and witness for justice.

More than half a century later, his shadow stretches across courtrooms, classrooms, and communities. The boy who memorized the Constitution as punishment grew into the justice who forced the country to live up to it.

And in doing so, he gave America not only its first Black justice but also its enduring conscience.

Please consider supporting open, independent journalism – no contribution is too small!

I am so grateful that Mr. Thurgood Marshall through his work and knowledge gave us a better nation.

Beverly, thank you for reading and sharing that thoughtful reflection. Justice Marshall’s legacy truly made our nation stronger — showing how knowledge and courage can create lasting change. We appreciate your support of The Truth Seekers Journal. Please consider subscribing and contributing to help us continue telling these important stories.

I had the great honor of meeting Justice Marshall a few years before he passed away. I was a young Staff Assistant working for a member of Congress. My boss and the Congressional Black Caucus (CBC) invited him to speak at the Capitol. It was my job to escort him into the waiting room and assist him until he was ready to speak. We had polite conversation, but he was a little grumpy. When I took him to his seat, they turned on the flood lights. Much to my surprise he yelled, “get those goddamn lights out of my eyes”! Although I was surprised, I smiled because I said to myself self, this man has been a tireless advocate for black people and indeed all people for most of his life! He had to fight all of his for equal rights. At that stage in his life, I thought that he had earned the right to be a little ornery.