By Milton Kirby | Decatur, GA | December 22, 2025

The Powerball jackpot has surged to $1.660 billion, placing it among the four largest lottery prizes in U.S. history and igniting another nationwide wave of ticket buying driven by hope, habit, and long odds.

The winning numbers from Saturday, December 20, 2025, were 4, 5, 28, 52, and 69, with the Powerball 20. No ticket matched all six numbers, pushing the jackpot higher ahead of Monday night’s drawing.

As lines stretch across convenience stores and gas stations, the spectacle once again raises a quieter, persistent question: who is actually funding these billion-dollar jackpots—and who benefits most from the system behind them?

A Jackpot Built on Millions of Small Bets

When Powerball jackpots climb into the billion-dollar range, economists estimate tens of thousands of tickets are sold every minute nationwide, with sales accelerating sharply in the final hours before each drawing.

In Georgia, those sales flow through the Georgia Lottery, which operates through roughly 8,500 retail locations statewide. Proceeds support education programs such as the HOPE Scholarship, HOPE Grant, and Georgia Pre-K.

Since its creation in 1993, the Georgia Lottery has generated more than $25 billion for education, a figure frequently cited by lottery officials as evidence of public benefit. Research shows, however, that the source of those funds is far from evenly distributed.

What the Atlanta ZIP Code Maps Show

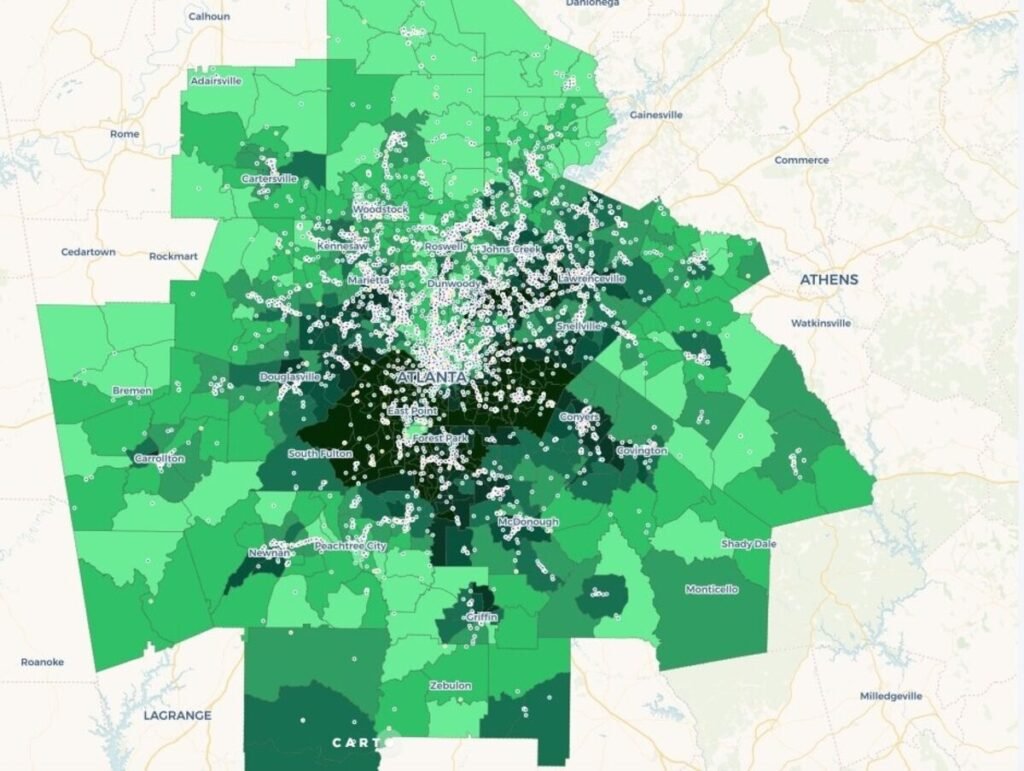

Visual mapping of Atlanta-area ZIP codes tells a consistent story seen in academic studies nationwide.

Lower-income ZIP codes in South DeKalb, Southwest Atlanta, and parts of South Fulton show higher concentrations of lottery retailers and higher per-capita ticket purchases. By contrast, wealthier areas in North Fulton, North DeKalb, and suburban communities show lower per-capita participation, even when absolute income levels are higher.

Researchers affiliated with Georgia State University and other institutions have found that lottery spending increases as median household income declines. Retail density, advertising visibility, and consumer participation all rise in economically stressed neighborhoods.

Economists describe this pattern as a regressive funding structure, in which lower-income households spend a greater share of their income than wealthier households.

A National Pattern, Not a Georgia Exception

This dynamic extends far beyond metro Atlanta.

Studies cited by the Urban Institute and the Brookings Institution conclude that households earning under $30,000 annually spend three to ten times more of their income on lottery tickets than households earning over $75,000.

Lottery participation is highest where economic mobility is lowest, and where sudden wealth appears most transformative. As jackpots rise, those disparities become more pronounced.

Who Benefits From Lottery Funding

While lottery revenue is raised disproportionately from lower-income communities, the largest education benefits often flow elsewhere.

HOPE scholarships and grants are most frequently claimed by students who complete high school, meet GPA thresholds, and attend college. Those outcomes are more common among middle- and upper-middle-income households, which tend to have stronger academic preparation and access to resources.

The result, economists argue, is an indirect upward transfer of wealth, even when lottery funds are directed toward public education.

Billion-Dollar Winners and Long Odds

The scale of modern jackpots is a relatively recent development. Earlier versions of Powerball included jackpot caps and better odds. Structural changes extended the odds dramatically, allowing jackpots to roll over longer and grow larger.

That evolution culminated in 2022, when a $2.04 billion Powerball ticket sold in California became the largest lottery prize ever claimed. The sole winner, Edwin Castro, opted for a lump-sum payout of $997.6 million, according to the California Lottery.

Those rare wins dominate headlines, while millions of losing tickets quietly sustain the system.

The Lottery’s Counterpoint

Lottery officials and defenders argue that participation is voluntary entertainment rather than taxation, that proceeds fund voter-approved education programs, and that scholarships and Pre-K deliver measurable public benefits across the state.

They also note that without lottery funding, education programs would likely require alternative taxes or face reductions. Critics respond that voluntary participation does not eliminate inequity when spending patterns align so closely with income and geography.

Hope, Math, and Public Policy

For many players, the lottery represents possibility more than probability. Behavioral economists point to optimism bias and financial stress as powerful motivators, especially during billion-dollar jackpot runs.

The math, however, remains unforgiving. The odds of winning the Powerball jackpot are roughly one in 292 million.

As Georgians line up for the next drawing, the growing jackpot reflects a national reality: billion-dollar dreams are built from millions of small wagers, many placed in communities that can least afford to lose them.

Support open, independent journalism—your contribution helps us tell the stories that matter most.